Patient Preparation

Feedback

Keyword matches are highlighted.

It is essential to:

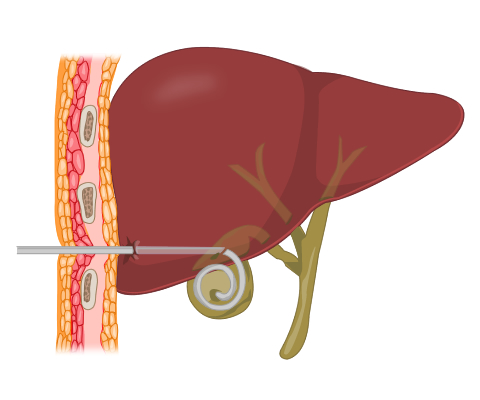

- Review all available imaging to confirm the indication for the procedure. It also helps to assess gallbladder anatomy and establish safe access route to the gallbladder

- Check full blood count and coagulation profile to assess the risk of haemorrhage

- Obtain informed consent for the procedure

- Obtain good peripheral IV access

- Administer broad-spectrum IV antibiotics 1-4 hours prior to the procedure. Septic patients are often already on parenteral antibiotics

- Arrange analgesia and sedation according to patient comfort

Remember, patients with jaundice often have deranged liver function and abnormal clotting. Check platelets and coagulation before going ahead.